On the engineering genius of Daft Punk

Lose Yourself to Engineering?

It’s fairly safe to say that 2013 was Daft Punk’s year. They brought out, to great hype, fanfare, and reviews their latest album, Random Access Memories, which made it into third place in The Guardian’s “Albums of 2013” list, behind John Grant’s Pale Green Ghosts in second and - in their opinion - Kanye West’s Yeezus in first (for the record)°.

I listened to Random Access Memories intently over the weeks following its release - and hated it. Then I loved it, finally settling for an awed respect. Nobody could put it better than Sasha Frere-Jones at the NYT: _“The duo has become so good at making records that I replay parts of ‘Random Access Memories’ repeatedly while simultaneously thinking it is some of the worst music I’ve ever heard… Does good music need to be good?” _ The opener, Give Life Back to Music comes across as an all-too respectful homage to 70’s funk, without adding anything to new to music at all. Yet, filter away the actual tune, inspect the nuts and bolts of the whole album and you’ll find so much to admire in the way it’s been assembled. It’s a damn fine engineering job.

Music is my main hobby, so with access to all the power that Cubase provides, I could conceivably compose and then produce something along those lines (though I emphatically don’t work in that direction).

Despite those bold words, though, I’m still fairly terrible at production, which is music’s engineering. A music producer (or audio engineer, as they are also called) has to work on ensuring that:

- voices (human or instrumental) have their own place in the mix,

- are clean and tidy, or dirty and scruffy, as desired;

- no frequency is overloaded, or uncomfortable to the listener

As I say, I’m not very good at it. Whilst I can appreciate a good mix, I tend to desensitise my own ears by overlistening to my own mixes, always wanting more (when less is by far the better way) andthereby muddying the sound to a point where it sounds acceptable to me on my own headphones, but is a disaster on loudspeakers, for example.

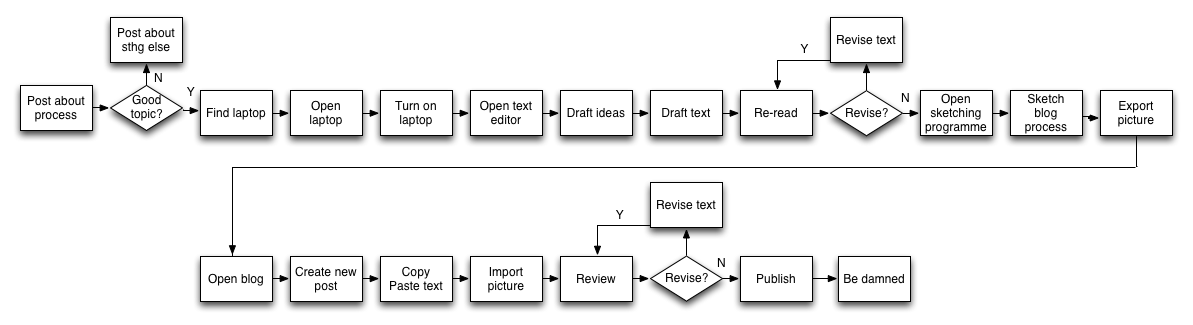

Music production consists as much of a workflow as product engineering does and goes something like:

- Audio mixdowns (exporting each track, whether synth, samples, humans or tubas into an audio file)

- Post processing:

- Panning

- Levelling

- Equalising

- Loudness

- Compression

- Distortion

- Reverb

- (and much more)

- Testing

- Ensuring that none of those frequencies are overblown

- Making sure no voices are lost

- Validation

- pre-mixes

- album-wide sound levelling

- Final mix

- mastering and publishing

- (gulp!)

For each step, the producers have a vast array of tools at their disposal for each step, but final quality control can’t be quantified away - it’s still in and between the ears.

Daft Punk had three things going for them in this intrepid exercise: lots of experience, a huge budget and a big team. Now, whilst the duo weren’t short of a penny or two given their back catalogue, it was still a massive investment on their part to go down the rout of maximising the human aspect of this album. It ended up being a massive, globally managed project, with all of the collaboration, communication and data transfer challenges that such an enterprise generates.

And all of that for, musically, a rather dull record.

It takes me back, perhaps controversially, to my days working as a packaging engineer at Ford. It was part of my graduate induction programme at the company and, if I’m honest about it, I felt that it was somewhat beneath me. Putting parts into boxes? What’s “engineering” about that, then?

All of it. It was, in reality, a complex puzzle that needed to be completed against time whilst ensuring the safe arrival of pretty much each and every single possible component in a car after transportation across half the world, with all conceivable qualities of route. More than that, the product and methodologies were endlessly optimisable.

So, working as part of a large global team, with a big budget, complex problems to solve, worse problems lurking behind any cut corner and bad, vending-machine coffee on offer, I came up with… a cardboard box.

If you’re in that situation, too, remember Daft Punk and Random Access Memories - your product may, superficially, be dull to much of the population, but, if you end up Doin’ It Right, it will sound great.

Happy 2014!

°(alright, and perhaps for a small boost in search engine findability, too… :-))

Engineers have an often uneasy relationship with words. The common assumption is that if left to our own devices we'll mangle grammar, butcher words and generally leave a trail of linguistic destruction in our wake. This is largely unfair, as stereotypes tend to be, but we are rightly better known for our smithing of iron than of prose. If we think about language at all, it's usually in the sense of grudgingly having to cope with it, or even wishing it away: "we shouldn't bother too much about writing - it's the product that counts."

Engineers have an often uneasy relationship with words. The common assumption is that if left to our own devices we'll mangle grammar, butcher words and generally leave a trail of linguistic destruction in our wake. This is largely unfair, as stereotypes tend to be, but we are rightly better known for our smithing of iron than of prose. If we think about language at all, it's usually in the sense of grudgingly having to cope with it, or even wishing it away: "we shouldn't bother too much about writing - it's the product that counts."

After letting lady Shanghai go first, gentlemanly North America, along with cousin Mexico, took its turn at being trained by a bunch of know-it-all Europeans (and one Australian), who were airdropped into Detroit last week to bring a breath of fresh thinking to the way our product and processes are treated, and to help make this new air the one we all breathe globally.

After letting lady Shanghai go first, gentlemanly North America, along with cousin Mexico, took its turn at being trained by a bunch of know-it-all Europeans (and one Australian), who were airdropped into Detroit last week to bring a breath of fresh thinking to the way our product and processes are treated, and to help make this new air the one we all breathe globally.