Continuing my observations on being a working, playful engineer: you can read the introduction in Part 1

Time flies when you’re in the lab

I recently read, in a borderline mystical article about the Taiwanese chipmaker TSMC over on Wired, the phrase “time flies when you’re in the fabs” (production plants where microchips are fabricated). Substitute the ‘f’ in “fabs” with an ‘l’ and you have the same for me in the lab… sort of.

In that article, the time-flying stems from the sort of sensory overload we experience when visiting a new city or a factory for the first time: the quantity and intensity of new inputs and interactions can overwhelm our mental processing capabilities and it’s tricky to know where to focus our attention.

For this effect to take hold in a calm, familiar lab we need other stimuli, something unusual to happen, to kick us out of the routine and into a mode that could (until a technician reminds us) lead to us forgetting that it might be lunchtime. We need play.

The lab for the development engineer

It perhaps doesn’t sound right to associate a lab with play, this agile alertness that brings joy and satisfaction to an activity, and there are certainly some instances where, as you might expect, the conditions necessary for play simply aren’t there: we’re repeating a totally standard test on standard parts for re-qualification. In other instances, excitement occurs, but not necessarily play (quality investigations spring to mind, alas).

For me it was as development engineer that my playful relationship with the lab really became most apparent. Setting out to produce something new from an initial idea gets the creative juices flowing, the mind whirring. Extending this into the lab is brilliant: not yet knowing if parts can be tested with current equipment, not knowing what the results will be (even if we have hopes or technical expectations for what they should be), uncertainty as to how representative of a potential final product the initial prototypes will be all gets us thinking, imagining, tinkering, bouncing ideas off others in the team. At this exciting stage we’re a long way from expecting pass/fail reports or sometimes even answers: we’re finding out what the questions should be, we’re in the phase where interesting results are to be found in the realms of “promising,” “so-close…,” or “so far off…": results that lead to further ideas and testing.

Playtime!

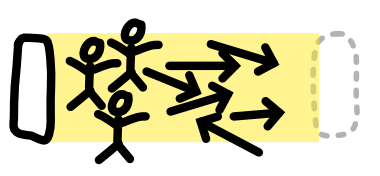

These are my most “alive”, most playful moments in the lab, with multiple phases and objects (in the grammatical sense of people and things) of attention: chatting with technicians, handling parts, checking drawings and the test rig, figuring out how samples might be mounted, whether we need new fixtures (if we do, and we need to order something, playtime quickly ends!). The lab technicians may have encountered similar ideas in the past and warn what their weaknesses were. This is where the ‘plan’ (the official test request that I wrote back at my desk, in the past), meets a reality which is starting to become “now”, and need knocking into shape to bring closer to practical reality.

Starting the test entails switching attention from the personal and the physical to the informational: whilst still operating keys and switches and clicking a mouse button, still discussing with the technicians, we’re opening the appropriate programs, ensuing all the settings and parameters are right for this test (they may be totally custom, or tweaks of some existing presets), priming the data logger to start upon a certain trigger signal, and then pressing some kind of ‘start’ button to run the test.

Finally the test begins: I’ll have my hopes, fears and expectations, and (if I’m in the lab whilst testing is under way) I’ll be weighing up the results against those expectations as they come in. I tend to be unable to avoid interpreting every single result as it comes in, pondering already - too soon, but in preparation - their meaning, and of potential repercussions or next steps in the product’s development, whilst actively reminding myself (part of an engineer’s training and experience) to avoid reading too much into the insufficient data that we currently have… If I’m helping with the test (usually a bad idea, but sometimes necessary), I’ll be petrified of missing a step, but too distracted by the results to be able to calmly concentrate on my tasks, so sometimes I’ll make mistakes. Equally, though, if I see a totally unexpected result come up, I’m on hand to discuss it straight away with the lab technician, ready to test hypotheses and to come up with a plan on the fly.

For very slow tests (the archetype for me here being corrosion testing), those doubts and expectations surface from time to time at unexpected moments, the spirit of the test spooking me from where I sit, calling me back to the dungeon - I mean lab - to check up on the parts, peeking into the chamber to reassure, or to terrify myself, before the official end of the test, all the while being aware of the suspicion of influencing the test by the mere peeking inside…

This is all part of the game, aspects of play.

Not play

Typically, for me, the sense of play is over long before the full test is finished: testing itself quickly becomes routine and requires that different mindset and expectations of a technician. As hinted at above, a key difference between someone like me and an experienced technician is that they typically don’t let themselves get distracted by results, and can - we could say stoically, though it often seems more simply to be their nature that drew them to this job, rather than any additional philosophical system modifying their behaviour - just plough through the testing, seemingly effortlessly concentrating on testing each sample correctly.

This raises some interesting questions about games and play: surely there are games that require quiet concentration, the ability to avoid distraction and still be able to react to variance? Yes, of course! My counter to this point is that, if the prior play has been successful, and the test runs well, then you could put any practised technician in to run the test itself, without any knowledge of the parts or the origin of the test: it’s routine that wins, not reactivity or any particular alertness.

Indeed, under certain circumstances, I would run the test myself. There are aspects of this that I appreciate: handling the parts, knowing their type and expected performance, I observe and register many things, almost like a craftsman; the same with the test rig and mounting the samples for each test. Yet this doesn’t feel playful to me: it’s careful and precise, but doesn’t require the alertness or the ability to bring in factors from all sorts of sources for it to work. It just does work, and can (should) be a bit of a plod.

Usually, the end of the test also doesn’t feel like play: it’s mostly loosening things and removing samples from the rig. Typically, we’ll look at a few of them to see if anything unusual happened to them, visually; if it’s an unusual batch, then I’ll keep them all for possible analysis afterwards. It’s the analysis, interpretation and presentation of the results where the playful can re-emerge.

The philosophical playoratory

It’s in such an appropriately equipped, ideally local and freely accessible lab (rather than an external test centre), where you know the colleagues and can take the time to discuss things with them, that a lot of what makes engineering so appealing come to life: bouncing ideas off each other, deciding what tests to run on which parts, what equipment to use, who would be the best person to do the testing. Phrases like “oh, let’s try it in there” or “could we perhaps…?” or “let’s test a couple of parts, see where we stand”, or “how do we get this to fit?” and “do you think we’ll be able to see if…?” represent play in the lab.

Analysis of the data or of parts after testing can also be playful, the classic example here being the microscope: “check there,” “zoom in to that”, “measure that bit there” - but of course with the same phrases being applicable to charts and data - always trying to figure out meanings and implications.

When I consider my interactions with the lab, things get philosophically complicated and interesting, with multiple relationships and perspectives manifesting at different phases during a test, and, sometimes, all at once. Here’s a list of the semi-philosophical aspects that flicker in and out of attention in the lab context:

- My relationships with colleagues

- Philosophically related to politics, practice and ethical action

- My relationship with the parts

- Those parts and their multiple meanings and implications are present physically and (differently) in my mind. In both contexts are they real entities on which I imbue real concerns and hopes. I sense them and I imagine them.

- Philosophically related to the perspectives of…

- practice and technique

- phenomenology (understanding how we experience and interact with others, along with borderline metaphysical considerations of “reality”)

- ontology (understanding what is, and how it is)

- epistemology (knowing what we know about the part, and what we still don’t, and want to know)

- My relationship with the test equipment

- direct (if I do the testing myself)

- indirect (if the technician does the testing for me)

- knowing its strengths and weaknesses, relationship with “real world” use

- Philosophically related to…

- My relationship with the test process / procedure

- determining steps in advance: planning

- being alert and open to possible changes as they come in

- action

- My relationship with pretty much the whole of history (or at least the history of science and technology)

- how we ended up with these machines, parts, means, methods and levels of understanding

- My relationship with the “background technologies”

- Paper, screens, mobile phones, furniture, buildings, infrastructure

- Fans, coolers, data networks of the equipment being used

- Test rig consumables

- My relationship with the data

- Philosophically…

- hermeneutics

- epistemology (how do I interpret the data, what knowledge and experience do I already have that permits me to understand what the data is telling me in this particular, hopefully productive, way)

- phenomenology (how am I viewing the data, how are they mediated)

- The overarching experience of testing

- Full suite philosophy

As we can see above, the lab - and engineering - is full of the key perspectives of philosophy (that I’m aware of, anyway, discounting metaphysics):

- Hermeneutics - interpreting requirements, procedures and results

- Phenomenology - “feeling” and experiencing the parts, through your eyes and modulated through instruments

- Epistemology - assessing the current knowledge about a thing, trying to figure out what’s not yet known, and how to know it, how confident we can be in that knowledge, and how to deliver that knowledge to others

- Politics and interaction (and a kind of technological ethics) - dealing with lab technicians, lab managers, getting timing commitments or confirming resources, dealing with problems

- Maybe some ontology, as an overarching concept? What exactly are these things and tools we are dealing with? How do they exist, what becomes of them during and after testing? What are our affordances, what can we use, manipulate to our advantage, ensuring power and data connections, temperature conditions, etc

These perspectives all intermingle, and attention flickers between them. I, as a non-philosopher engineer, have a lot to learn from them, which is why I’m here, writing this!

Play anywhere!

This extended reflection on my experiences in the lab is only one example of how work-time play can arise. The phrase “productive meetings” doesn’t need to be an oxymoron: ideas really can arise out of playful action, even in a meeting environment.

Don’t discount non-work play at work

Another form of play - equally important, in my opinion - is recreation. Ultimately, this is about restoring body and (in our case, in the work environment, more significantly) brain to be ready for the next pulse of work. Our brains really do get tired, gum up with waste chemicals that need removal or simply need more fuel, after all. But we, as humans, also need to tend to our groups, teams and societies - so that lunchbreak the technician reminded us of earlier is important in this way, too.

Documentational drag

In engineering, as at home, playtime is often over swiftly. Data gathered from the tests needs to be summarised and reported; completed, those reports have to be saved in the appropriate library for future reference - tagged and searchable so that future colleagues have a chance of finding what their predecessors got up to in the dim and distant development of those tests, products and processes. And, of course, the physical needs to be tidied up, too - a fundamental part of play, but not, as far as I experience it, play!

From play to mastery

Another aspect to consider is that the goal of work is mastery: knowing what to minimally adjust to achieve the maximum desired effect. Mastery is a calmer version of play, secure in the knowledge that what you’re doing is right (and good), but retaining that awareness and reactivity to adjust to any small deviations.

Just as there are various perspectives to focus on whilst mastering a musical instrument (sound, agility, improvisation, etc) - or even, come to think of, a measuring instrument, there are ways of mastering engineering topics and systems that aren’t purely technical, but require that playful agility, that personal phronesis, way of acting, that has become such a key part of my thinking on engineering.

Once mastery has been achieved, though, the goal of a company is often to move back beyond mastery to renewed play - to build on the already-mastered to expand its competencies and to stay ahead of the market game. This is an institutional challenge that goes beyond the individual, but it relies on individuals to recognise that necessity and not to succumb to the deadening constraints of overspecification and the mere passing of audits.

Getting back into the game

I’d like to end on a personal note: as I mentioned in my penultimate post, I’ve been between jobs for a while. I can now report that as of May 2023 I’ll be getting back into the ring, in a new arena, with completely different products to those that I used to be involved in making. Fortunately my new employer recognised the skills and experience that I will bring with me to their game, and I’m looking forward to making use of them once more. But most of all, I’m looking forward to playful engagement, moving things forward with a new team, in perhaps unexpected, but fruitful ways.

Everything's perfect

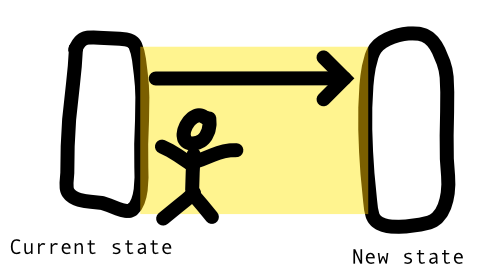

Everything's perfect

But wait... there is something that needs doing!

But wait... there is something that needs doing!

I did a thing!

I did a thing!

What to do?

What to do?

Meandering through the day

Meandering through the day

Constraints keep us and others safe

Constraints keep us and others safe

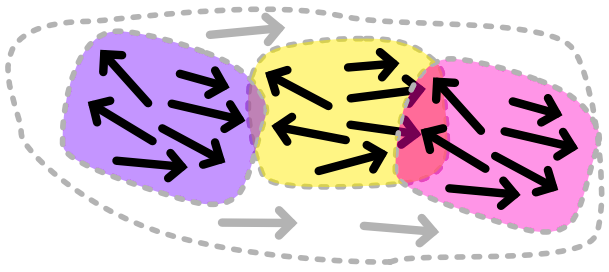

A group of people, a jumble of actions - sometimes in general alignment

A group of people, a jumble of actions - sometimes in general alignment

Groups interact with groups... politics happen

Groups interact with groups... politics happen

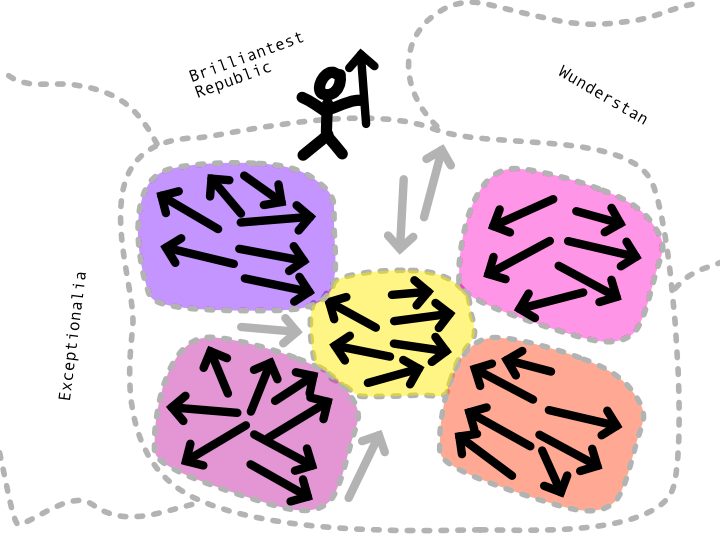

Aren't authoritarian autocrats exceptionally lovely?

Aren't authoritarian autocrats exceptionally lovely?