About work - a field perspective

A post from one of my previous personae, Literally Engineering, from November 2020. I keep coming back to this one, and feel that the overall idea stands up well.

A field perspective of work and politics

Why think about work?

I was going to write about applying engineering methods to philosophy (I still plan to). Trouble was, as I got further into it, that post became more and more unwieldy as considerations popped up like: what are tools? and: what are engineers? (Philosophy, eh?) Since engineers work (as in - it’s our profession) that’s how I came to start writing about work itself, to provide a basis for those questions that, I hope, will let themselves be written about a little more easily.

Remember: this a blog post, so it’s not definitive and I’m sure to return to the idea once I’ve read more into it (I’ve also just started reading James Suzman’s Work: A history of how we spend our time) - but… here goes!

Work: what is it good for?

Fulfilling, defining, meaningful consumer of time; a source of satisfaction, stress and sleepless nights, of distraction from the finer points of life, or of structured relief from the chaos of family and friends, all of whom can also be… hard work. That’s work.

Have you had that experience, that if you fixate on a word in your mind for too long, it suddenly sounds ridiculous? “Work” ends up sounding like a frog’s croak or something. But before it reaches that stage, “work” can stimulate all kinds of hints and notions and emotions, whether we focus on its meaning as a verb or as a noun, or let it flicker between the two. Professions, occupations, undertakings, jobs, roles, tasks, responsibilities, duties, even hobbies and maintaining relationships: all these forms of work are, fundamentally, as in physics, a question of energy transfer.

Without a potential or a gradient, energy will not flow. And in the case of work, without a start signal, nothing will cause that potential to rise. That potential is of a mental, emotional nature that can, at a certain threshold, signal the pumps to start up so that energy can be transferred to whatever objective we have in mind.

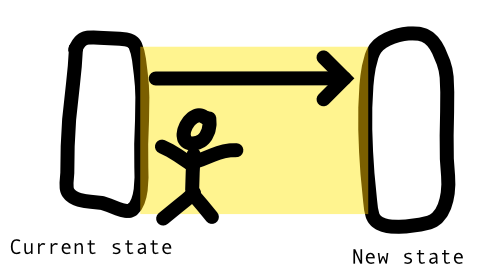

The signal, the “programming” of the operation and the action itself involve the bridging of some gap between a current state and a future imagined state. All of that together builds “work”.

Building up the model (this is also work)

It is feasible, if unrealistic, to consider the future imagined state being precisely the same as the current state (the defining word here being “imagined”). Practically speaking, we might think of this as being the notion of maintenance activities, but maintenance is still “real” work, requiring energy. For this “zero work” scenario, we would have to imagine someone sitting in a pleasantly perfect state, with no improvement or activity imaginable. Or someone who was dead, but that path doesn’t appear to lead to any useful conclusions.

Here’s what it might look like:

Everything's perfect

Everything's perfect

This state can only last to the point at which our character becomes bored, or uncomfortable, or wet or cold, or hungry, or needs relief from previous digestive activities. A tension arises, which spans the current scenario and an imagined future state:

But wait... there is something that needs doing!

But wait... there is something that needs doing!

The tension of intention

Right now, that character can “see” and hold a new, imagined, state, in mind - a “field of intention” sounds about right as a name for this - but nothing happens yet beyond some highly complex neurological and physiological changes that prime our character for action. Mental maps are generated of where the action should take place and where appropriate utensils might be found, a general concept of how the action might be completed is mentally sketched, as is an assessment of how much energy might be expended during the undertaking - which can also lead to the conclusion: “ah, forget it”. It’s only when an action occurs, however, and physical energy is expended, that the tension can be resolved, as in the sketch below:

I did a thing!

I did a thing!

The arrow represents some kind of action, and the new state is now “real” - though it may or may not be the one that was imagined. Smashed cups, bleeding fingers or unsaved work being lost are not generally part of our imagined states, but they happen.

There might be complications…

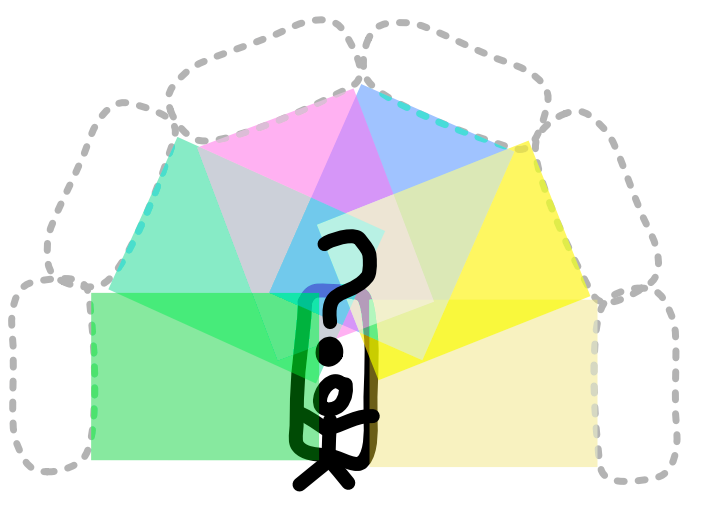

Of course, in real life, things aren’t as simple as a single pairing of state and new state: there are near unimaginable possibilities for work and potential new states are bubbling up continuously and almost simultaneously in our minds - a major stress factor in life is often “what to work on?”:

What to do?

What to do?

Sometimes the answer is clear, sometimes not. Sometimes just doing nothing is… very appealing. Typically, it is rare that we can complete one task to the exclusion of all others. In the course of a day, for example, we’ll meander from task to task, completing some, making progress on others, ignoring others still.

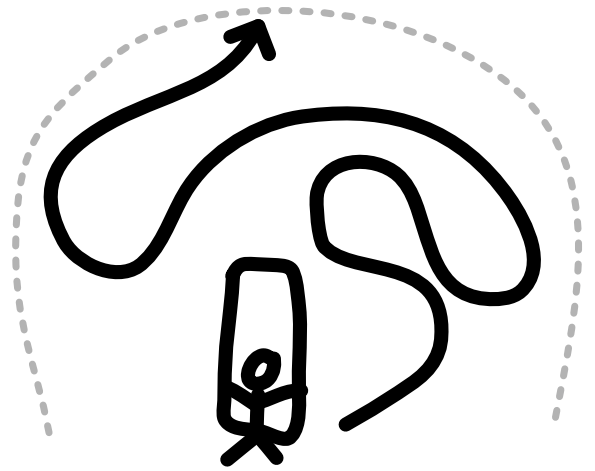

Meandering through the day

Meandering through the day

Each point along the meandering path actually represents a new state, where new possibilities arise, leading in some cases maybe to the sudden elimination of one possible task, or perhaps the creation of several more. This results in the “bubble” of imagined states taking on a different form (or, at least, content), with different intensities, at any point in time.

It’s the intensity, felt or understood emotionally as well as rationally, arising from all of these potential futures and actions that drives our decision making

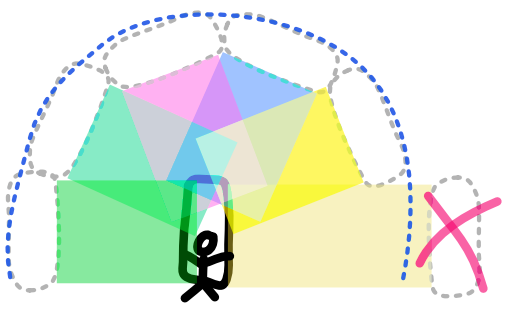

Constraints set us free

This is not the place to discuss in depth the notion of freedom, but it seems pretty clear to most of us in these pandemic times that freedom to act also requires ensuring the safety and security of others to act. This implies social constraints that allow us to act upon our fields with confidence (because we and those around us know what is right) or - if we have nefarious or illegal intentions - we have to have to act below or around constraints, in secret, for example. These constraints also condition the array of imaginable future states.

Constraints keep us and others safe

Constraints keep us and others safe

This all brings us to the next point in this - up to now - very simple sketch: other people.

If operating in society is sociable, then even engineers are sociable

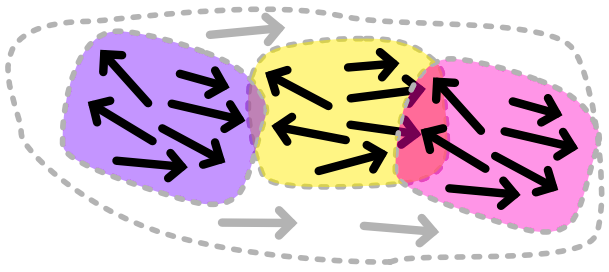

Fortunately for most, to the chagrin of others, we humans don’t live or operate in isolation. We live and work within groups that build fields of tensions. Sometimes those tension fields align, and are complementary, like “we’re all hungry”, or “our spears are rubbish, we need new ones”, or “we should invest in education for our children” … and actions based on those tensions arise, not all of which - it has to be said - are complementary or coordinated, but the overall vector of which can target the imagined state:

A group of people, a jumble of actions - sometimes in general alignment

A group of people, a jumble of actions - sometimes in general alignment

These groups may be small or large, and come from all ends of the spectrum of human activities. Some groups will be our employers. Other groups may be colleagues in other departments acting as further constraints (Finance! Sales! Purchasing! Legal!). Groups can be companies in competition within an industry, or from different fields mutually assisting one another (e.g. engineers and medics), or mutually opposing each other (environmental activists and fossil fuel energy companies).

As groups encounter other groups, societies build up, and the fields of tension become more complex still. Politics arises (also, by necessity, within our companies of employment), providing guidance and structure / infrastructure, as well as constraints - and gets messy:

Groups interact with groups... politics happen

Groups interact with groups... politics happen

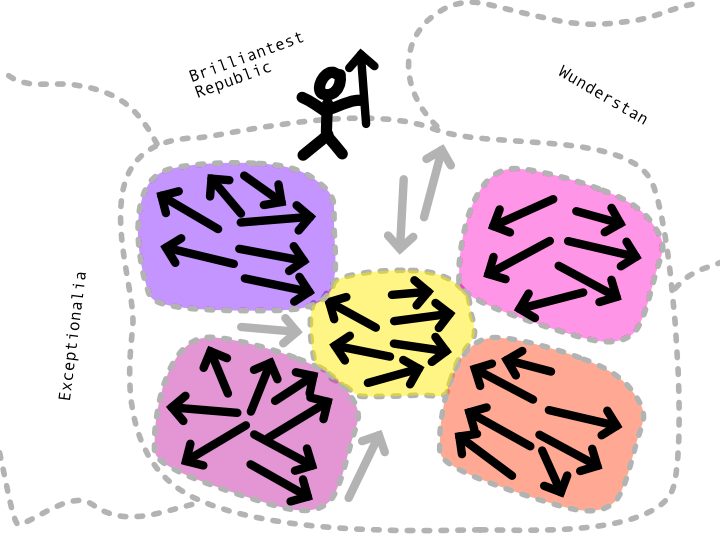

Sometimes societies are largely peaceful and are able to maintain a way of life via consensus and legitimate state power: some permit autocrats or populists to come to power, who need to create and highlight enemies both from outside their society, and from within, usually distinguished by race or religion (sigh), who need to be subjugated or expunged:

Aren't authoritarian autocrats exceptionally lovely?

Aren't authoritarian autocrats exceptionally lovely?

Pictorial rant aside; In any case, ideas arise from groups or individuals and need recruitment of others to perform actions with sufficient strength to achieve those goals. Recruitment also requires coordination or coercion, but these are ways of guiding or moulding the “intention field” of others.

The future imagined state from here?

The future imagined state of this blog is to have posts on what are engineers, what are tools, how the two interact, and, ultimately, for this series at least, to return to the original idea of applying engineering methods to philosophy.

Thinking back to groups: can they completely bypass each other? Perhaps, but it seems that technology and the engineers who develop it are a link to pretty much all areas of activity in the “developed” world. Think birdwatchers without the creators of binoculars or monster telescopic camera lenses. And that’s where I think we can fit engineers into society - who will be the subject of my next post.