Simondon Central

Backburning philosophy

Research, processing, writing. That’s how I would say writing basically proceeds, even in fiction. I was going to say something condescending about my schoolboy self as an exception to that rule, considering the English essays I would dash off on Sunday afternoons for homework. But even then, the three phases were there, I’m sure; it’s just that any temporal distinction between them may not have been particularly discernable. Research may sometimes (OK, rarely) have involved fact-finding; at other times it was about coming up with a story arc that might satisfy the requirements of the homework that had been set. Processing was imagining chunks of narrative and how they might connect and flow; writing was getting it all down onto paper - perhaps a sentence or a paragraph behind the other two phases.

These days, I’ve tended not to get beyond the research and processing phases at all; writing got lost, subsumed into the research and processing phases as note-taking; all of which is merely safely satisfying, because there is no output and as a result, no readers to worry (about). The notion I had of learning and writing about the philosophy of engineering (PhoE) remained on that backburner. Now, though, I have decided to add some energy to it, to break that study-cycle, and write.

But, where to start? I’ve been reading and reading. My mindmap has become ever more complex, my notes go back months and often don’t mean much now. I have generated too many diffuse thoughts about it all and I needed a good anchor point, or a central station as a starting point for this journey, a beginning. Fortunately, that beginning has been with me for a long time, and has a name.

Gilbert Simondon

Infuriatingly, I can’t recall exactly how, when or why I ended up “discovering” Gilbert Simondon. The earliest reference from my own notes that I could find of him is from back in 2012. This would, I think, have been shortly after a chat I had with a philosopher friend - a Frenchman - who had first puzzled me with the word “epistemology”, which I’m sure set me off on a Google search along those lines. That word had also set thinking of possible titles for an engineering blog I thought I might want to write at the time. I created a list in Evernote of (in retrospect very silly) possible titles for said blog - and in that note I had referred to a work called “La question de la technique” from Gilbert Simondon. Perhaps in those days, he was a “thing” on the internet. Perhaps my friend mentioned him in passing: I don’t recall, but somehow the name stuck.

Returning to the subject now, it’s like he used to be a prominent waypoint marked on an ancient map; an obvious navigation aid. But now he’s gone. Like an eroded hilltop, he’s not remotely as prominent now as I had thought him to be.

Additionally, I have read (but not written) quite a bit beyond him; that served only to highlight how much he appears to have gained in insignificance: hardly anyone (outside the French-speaking world, at least) seems to share my initial enthusiasm for Simondon.

He is only granted a few lines by Carl Mitcham in his book Thinking through Technology: The Path between Engineering and Philosophy, for example, and none at all in Kevin Kelly’s “What Technology Wants. A Google search for “philosophy of engineering” or “philosophy of technology” doesn’t turf up any references to him; the Philosophy of Engineering Wikipedia page doesn’t refer to him at all. So how did Simondon end up as kind of my launchpad for the philosophy of engineering?

Well, he had written one of the most intriguing titles that I have come across, and I relatively quickly found a copy of an English translation of On the Mode of Existence of Technical Objects on the internet and started to read it.

It was baffling.

And intriguing. So I delved further.

Not much ado about Gilbert

Gilbert Simondon was a French philosopher and technophile who published his principal works on what I would call the engineering aspects of technology in the 1950s and -60s (he went on to look at more humanistic, psychological aspects later). During his studies in philosophy, he also took courses in physics and psychology. Carl Mitcham, in the book I mentioned earlier (Thinking Through Technology) notes in passing that Simondon was also a human factors engineer - but I couldn’t find any corroborating evidence of that, on Wikipedia, at least.

Simondon extended the idea of identity and technology’s place in the world to some baffling places, and there does now appear to be a hint of a new wave of thought stemming from Simondon’s work (de Boever et al’s “Simondon: Technology and Being” is an example from 2012). Bernard Stiegler, another Frenchman, refers to him occasionally, too.

But for me, the key text remains his early thesis “On the mode of existence of technical objects”, which genuinely does raise ideas that I feel are still relevant to our understanding of engineering.

About that mode of existence of technical objects…

As I mentioned above, Simondon's thesis On the mode of existence of technical objects, published in 1958, baffled me in 2019 (it’s a philosophical text, after all). But slowly and surely, some of its meaning has percolated through, and it does make a sort of sense. An initial stab at a summary would look like something along these lines:

- Simondon was writing to understand where technical objects might stand on a spectrum of things, from “natural” to “unnatural”.

- For him, technology was as human as anything that the Humanities produced. There was no need to differentiate between art and the artificial:

“Technology is full of human striving and natural forces.”

- Simondon was also interested in how technology developed from and is different to the artisanal crafts.

- In the crafts, tools are “merely” an extension of the human body. The human is also the sole source of information to the tool, as well as often providing much of the power.

- In the technological industries, power can come from nature and information from other machines.

In his element

The other topic that Simondon took on in this thesis was how a hierarchy of technical objects might look. He came up with (starting at the lowest level):

- Elements

- Basic tools and machines. Advancement of these elements leads (according to Simondon) to a 19th Century style of enthusiasm for improving humanity’s lot.

- Individuals

- Complex machines such as robots. Advancement here leads to defensive notions and worries about their taking over of our jobs: they appear to be competing with us

- Ensembles

- A combination of elements and individuals working under a highly-developed flow of information.

- Humans

- Master coordinators and - at a cultural level - interpreters of machines.Considering that he wrote the thesis in 1958, one phrase from the introduction seems remarkably prescient:

“The machine with superior technicality is an open machine…” {not merely as automated as possible} “…and the ensemble of open machines assumes man as permanent organizer and as a living interpreter of the inter-relationships of machines.”

Concrete, but not as we know it

Each technical object at each level could also be “rated” across another spectrum ranging from… and here it gets a little weird: from “abstract” to “concrete”. Again, an initial stab at summarising these terms would look like this:

- Abstract:

- Abstract objects contain structures that are dedicated to fulfilling one role.

- They are technically primitive, not far removed from the original thought of the inventor.

- I suppose we could think of prototypes and Version 1 products or processes as being “abstract” designs. They more or less do what the inventor thought they might - but haven’t yet evolved through encounters with all of their challenges in service or in their market.

- Concrete:

- Objects that are integrated and highly evolved.

- Structures and elements within a “concrete” object share roles (the classic examples from Simondon were the cooling fins for an engine also forming part of the load-bearing structure, or a water turbine also using the water that powers it to cool itself).

- “Concrete” designs are now Version 2+, becoming significantly more integrated and efficient.

Concrete is a terrible word for us non-philosophers, as it comes with Minecraft connotations: I automatically thought of it as measning blocky and low-res. This is admittedly rather unfair to the engineers and architects actually working with the material. But to me, “abstract” sounds like the higher level, (“higher-falutin’”) word.

My own take on the word “concreteness” is that it describes a spectrum of maturity: a Concept (“abstract”) versus a mature Innovation.

Also, whilst Simondon doesn’t appear to have been considering other constraints such as material usage, waste, maintainability or recycling, he certainly stated that he doesn’t expect any design to be perfectly “concrete.”

Too many words!

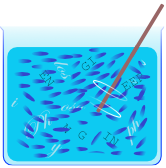

So many words! That was also a problem with the first edition of Simondon’s thesis - they didn’t allow for diagrams or sketches.

Here’s my sketch of an initial stab at trying to summarise the characterisation of Simondon’s maturity - complexity classifications:

I hope it makes some kind of sense - I’ll review it again over time and see what other tweaks I can come up with. Until then, enjoy now also having heard of Gilbert Simondon!