Report: an investigation into the enduring and endearing constraints of Report Writing

More than a few years ago, bordering on the “many”, I was invited to take part in a graduate selection weekend for Ford in the UK. It was a battery of tests ranging from one-on-one interviews and team-working simulations to presentations and problem-solving “incidents” – all nicely wrapped up in dinners and coffees in a pleasant hotel in the countryside.

One of the tasks – maybe there were twelve of them, I didn’t count – was to decide what equipment should be offered as optional, standard or not at all for a sporty Ford Escort model (these were the pre-Focus days), to meet a budget. We then had to write a report explaining our choices, needing to meet a most important deadline (lunch).

Being a bit of a car enthusiast, I made what I thought was a decent selection (including ABS and airbags as standard equipment), whilst keeping some budget for a few luxuries as standard (a CD player, I think), to differentiate Ford from, say, BMW, whose cassette tape decks were one optional extra, speakers to hear music from seemingly another…

Being a well-drilled undergraduate engineer, I wrote the subsequent report in the only way I knew how - with an introduction, a summary, a body and conclusions.

When I was given the job offer a few weeks later (which I took - a decision point that remains with me to this day, and is definitely worthy of a post of its own), Ford gave me some feedback over the phone. My presentation had been borderline terrible, but the report I had written was excellent.

In fact, it turned out that I had been the only candidate to actually write a report. Everybody else had written prose.

So, in honour of that, and in recognition of the possible fact that report writing remains for me, over emails and presentations, the main recipient of work related keystrokes, here’s my report on report writing in engineering.

TITLE

An Investigation into the enduring and endearing constraints of report writing

Author

The Literal Engineer

SUMMARY

The act of reading a technical report involves a certain mental effort. This effort should be rewarded with increased knowledge. In order to minimise the effort and to maximise the potential for knowledge extraction, the report writer should generate the report in as standard a way as possible.

The act of writing a report invokes a particular and peculiar mode of language, which itself requires a mental switch and effort to maintain, the passive voice. Writing in the passive voice lends the report an appearance (but no guarantee) of objectivity. A potential pitfall of the passive voice is the risk of the writing becoming stilted and unreadable. Yet this pitfall is deemed to present a lower risk to knowledge transfer than chatty and poorly applied novelistic writing.

Deciding on the tense remains difficult. The report should be written with history and evidence in mind; a report is a snapshot of the status of whatever is being investigated at the time, in this case – report writing. Using the passive voice is, overall, a positive constraint.

EQUIPMENT

Mid 2012 MacBook Air

2006 Rain Recording PC workstation with Logitech keyboard and mouse

Microsoft Word 2013 and Online

Microsoft Office 365 / OneDrive

Typepad blogging platform

Evernote note taking platform

Firefox and Safari browsers

1. INTRODUCTION

A technical engineering report can be understood as a window to a complex and meaningful event (or series of events) that took place within an organisation. The intended goal of a report is that its findings be understood. For this goal of understanding to be even remotely achievable, the report writer must describe the event in sufficient detail with sufficient brevity and clarity to form a synthesis of the outcomes of that undertaking. A report should therefore be logically structured and legible.

Ideally, the summary and conclusions from a report should add to the great body of human knowledge. It is recognised, however, that, more often than not, reports must be produced to describe small-scale and often painfully regular events.

Regardless of where a report lands on the scale of import (or lack thereof) to humanity, the form and language follow traditional structures. Report writing in the technical fields is designed to enforce (the impression of) objectivity. The passive voice depersonalises the investigation and can be construed as an attempt to prioritise facts over individual actions.

I did not post this report on 30th Sep.2014

rather:

This report was posted on 30.09.2014.

The tradition of using the passive voice imposes a constraint on the writer, which forces upon him or her (the passive voice at the very least enables authors to avoid the awkward distinction of the sexes) a mental switch and effort to make and to sustain the passive voice. This is an appropriate cost of entry, as the reader needs only recognise one style, whatever the source of the report.

2. THE STRUCTURE OF A REPORT

Reports are constructed around a common set of elements that may vary in style, format or order from organisation to organisation, but nevertheless ensure swift navigation to the pertinent sections or level of detail for the experienced reader - from an overall summary (usually to be found near the beginning), to detailed descriptions of equipment and methods used, via a logically structured body of evidence and discussion. The report at hand loosely follows such a typical structure and does not purport to set any standards with its own form.

It is also based on very little evidence.

3. THE CONSTRAINTS IMPOSED ON LANGUAGE IN REPORT WRITING

Actions and analyses leading to conclusions and summaries – no matter how breathlessly exciting at the time of their experiencing – are, in translation into a report, passed through a mental filter that compresses them into the passive voice.

This imposes a constraint on the author, which, similarly to the imposition of a recognisable structure on a report, lightens the burden on the reader (see Section 3.1 for more considerations on the reader’s role).

As in so many cases, especially in the arts and in engineering, this constraint can be viewed as overall positive: few physicists or engineers have been recognised as possessing the gifts of novelistic writing (or even spelling); honing the craft of the passive voice relieves these authors of many grammatical pitfalls.

The key to the passive voice, and the difference to novelistic writing, is that there are no characters or personalities to deal with. Someone or something does not do something to some other thing or person. Rather, some action is done to some object.

The strut was loaded into a tensile testing machine and its stress-strain curve was determined.

The sample was subjected to 60 cycles of cyclic corrosion testing according to specification X

The tea bag was placed into the pre-warmed cup. The cup containing the tea bag was filled to just off brim-full with boiling water. The assembly was left to stew for 4 minutes.

Humans act in all technical investigations, but the passive voice strips them out as being extraneous information. Whilst this is not always to be considered positive in most human relationships, being able to divide out the common denominators is, just as in arithmetic and mathematics, key to understanding the basic signals of what is being investigated. Humans, then, are a form of noise – in technical reports, at least.

Writing in the passive voice is a skill that must be honed with practice. For as long as the passive voice does not come naturally to the author, each sentence needs to be reviewed to ensure that the reader is not forced to stumble upon a person or a character rather than a description.

The implication of objectivity is valid. It doesn’t matter who did the test (especially in the sense of Professor vs. technician, or he vs. she): it’s not a diary. That information can be captured in lab notes, engineers’ notebooks, or the famous case notes from AT&T Bell.

3.1 THE BENEFITS OF THE PASSIVE VOICE

The passive voice is intended to portray the investigation as being impartial. This:

- enforces a certain mental discipline

- requires a certain mental “Umstellung” that brings the author into a standardised frame of mind.

- Permits the reader to read reports from any source in a similar frame of mind.

- Avoids “War and Peace”-style questioning of who was doing what to what other thing – no need to buffer names

- Personalities and their status are largely avoided

- The facts and conclusions come first

3.2 DISADVANTAGES OF THE PASSIVE VOICE

- It is easy to “hide” the contribution of laboratory personnel, lower level engineers, and so on, to attribute the report to one “star” player. This is more likely to be an issue in the world of university, where academics are forced to publish on a regular basis – a quality investigation on a returned part is less likely to be the cause of professional envy.

- Can be stilted, can become impenetrable,

- Enforces the use of some awkward words or constructions

4. SELECTING THE TENSE

A key decision that needs to be made early on in writing the report, one which generates some confusion, even within one report, is the tense. Some decision aids are suggested as follows:

- Tests are described in the past tense: they were performed (“the samples were tested using the tensile testing machine at yy mm / minute”)

- Results are described in the past tense: “the stress-strain curve Fig. x.y was generated”

- Findings may be either in the past or in the present tense:

- If a test was performed on a particular sample, e.g. investigating a failure, then the findings may be presented in the past tense:

- “brazing of the joint was found to be incomplete”

- If a test was performed on a particular sample, e.g. investigating a failure, then the findings may be presented in the past tense:

- If a result was fundamental, then the findings may be presented in the present tense:

- “the maximum tensile strength of the xx joint is YY MPa”

5. CONCLUSIONS

The technical report remains its own art form. Its art is knowledge and its form shall minimise the resistance to knowledge transfer. I really think that the passive voice helps to – oh, damn!

BIBLIOGRAPHY

http://www.sussex.ac.uk/ei/internal/forstudents/engineeringdesign/studyguides/techreportwriting

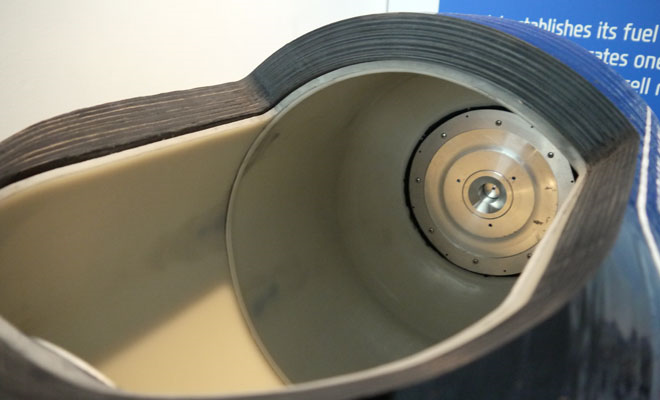

> Hyundai ix35 fuel cell tank cutaway. Source and permission: greenmotor.co.uk

> Hyundai ix35 fuel cell tank cutaway. Source and permission: greenmotor.co.uk

Toyota helped to kick off the 2014 CES show by

Toyota helped to kick off the 2014 CES show by